Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurological and developmental disorder that impacts the way in which individuals interact, communicate, learn, and behave. It refers to a broad range of conditions characterized by challenges with social skills, repetitive behaviors, and communication. Co-occurring conditions — including speech and occupational challenges, as well as gastrointestinal (GI) and sleep disorders — complicate the experience of autism and increase the complexity and cost of treating children on the spectrum. Today, one in 36 children are diagnosed with ASD in the United States, but that number has risen significantly over the last 20 years due to newly discovered indicators increasing the rate of diagnosis.

As more children are diagnosed, we have seen a surge of venture-backed deals in this space (more than $700 million in venture funding since 2017[1]). We believe this is driven by four key trends:

- Severe imbalance in demand for vs. supply of providers for autism diagnoses and treatment.

- Attractive reimbursement. All 50 states now require that Medicaid cover autism services, and a commercial plan that does not cover autism services is virtually unheard of. In addition, a child with autism often requires high volume of therapy.

- High in cost, vague on quality. Not only is prevalence and demand for services increasing, but payers are also often at a loss when it comes to what they are buying and whether the services they cover are effective. Autism as a share of medical cost is “completely out of control,” according to a payer in LRVHealth’s network of strategic partners.

- Lack of innovation. The private equity backed consolidation of mom-and-pop shops that has played out over the last decade has probably achieved some back-office efficiencies, but it did not touch things like cost, quality, outcomes, or patient experience.

History of the Space

The Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities act of 1990 created legal ramifications for failing to provide adequate care for individuals with autism, essentially paving the way for mandatory coverage of autism services. Several parent-led organizations drafted off of tailwinds created by these acts and lobbied the government to ensure children have adequate access to care. These lobbying efforts ultimately led to government-designed reimbursement pathways for Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) therapy. In 2001, Indiana was the first state to mandate ABA coverage. And in 2006, President George W. Bush signed the Combating Autism Act (CAA) into law which authorized nearly $1 billion in expenditures over five years for screening, education, early intervention, prompt referrals for treatment and services, and research of ASD.

In 2010, Great Point Partners acquired Autism Learning Partners, forming the first PE consolidation autism platform. This kicked off a period of private equity acquiring traditional mom-and-pop autism clinics and consolidating them into large autism clinic brands, a trend that continues today.

More recently, venture capital has also started to invest heavily. Where PE activities have focused on achieving back-office efficiencies, VC-backed models have focused on innovation in clinical delivery — most notably, consolidating various autism service providers under one roof and bringing forth new therapeutic models.

Landscape of Innovation in Autism

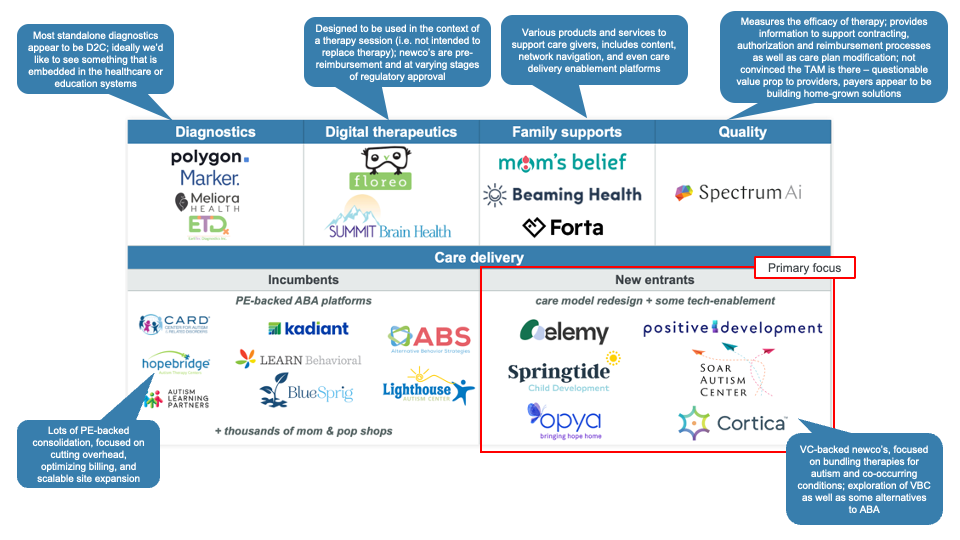

The innovation landscape covers diagnostics, digital therapeutics, family support, quality, and care delivery. We spent time in each category but decided to go deep into new care delivery entrants.

These new entrants typically offered three key value propositions:

- Access: They are, first and foremost, providing additional therapy capacity.

- Patient & payer experience: Most new entrants are creating a holistic care experience by consolidating several related services under a single relationship. For example, some companies offer speech and occupational therapy alongside autism services while others also offer medical services addressing areas such as GI and sleep. Not only is this a huge improvement for patients and parents, it is also beneficial to payers who are increasingly interested in underwriting a total treatment plan and having a single point of accountability when it comes to servicing these children.

- Cost management: If newcos can coordinate on the delivery of related services, then there are reasons to believe they can lower the total cost of care. The medical home enables a single provider to address a wider variety of the child’s needs which may lead to better management of interrelated issues that have a tendency to flare up like GI conditions. In addition, with a whole-person approach to care, it is plausible that the mix of services is tailored to the specific child and adjusted over time as his or her condition improves or evolves. Newcos are expressing an interest in developing alternative payment models around the whole-person approach. While the models vary (fees at risk, case rate, etc.), newcos are betting that through better coordination they can lower, or at least contain, total cost of care.

Stakeholder Perspectives

Patients/Families

For patients and families, the experience of autism is overwhelming. Not only are children and families challenged by the behaviors and communicative symptoms associated with autism, but there are also often sleep and GI issues that aggravate the totality of the situation.

Because a full diagnostic evaluation is time- and labor-intensive, it can often take months, if not years, for a child to be diagnosed with autism. And once diagnosed, treatment is a major commitment that can be disruptive and destabilizing to families. On average, children spend 20-40 hours in behavioral, speech and occupational therapy per week. These services are often disparate and uncoordinated, meaning that there may be no centralized understanding of a child’s current condition or progress.

Payers

Autism is an increasingly important focus area for payers because both the demand for providers and the cost of covering an autistic child are high. Couple that with the lack of quality infrastructure and a fragmented delivery system that is fraught with fraud, waste, and abuse, and you have a clinical category that is frequently viewed as out of control.

For most payers, network adequacy continues to be the top priority which means focusing on network development and credentialing more providers.

Cost and quality are also top of mind. Many payers utilize steerage and utilization management to limit the volume of out-of-network services and to ensure that they are not covering services that another constituent (such as a school) should provide. Payers also want more evidence that the services they are authorizing are clinically indicated. Unfortunately, the only opportunity for recourse for payers is when there are provable cases of fraud, waste and abuse. Without a widely accepted quality standard or operating model, payers simply don’t have a lot of control levers.

Finally, administration is a huge pain point. Due to the volume of services demanded and the fragmented, analogue nature of the provider system, payers spend a disproportionate amount of time administering the autism benefit.

Payers generally embraced the idea of bundling related services that newcos are offering. There was an intuitive belief that, in centralizing and coordinating care, the child’s conditions would be better managed, and this would lead to better member satisfaction and lower costs. There was also a belief that, in consolidating disparate services under a single provider, payers would enjoy some administrative relief.

However, there is still skepticism about whether this can translate into value-based care. Many new entrants in this space are designing value-based care products, but few are operating under these contracts today. While payers are notionally interested in paying for value and quality, they are not set up to manage a VBC contract for a condition as heterogeneous and poorly understood as autism. In addition, access and network adequacy still tops the hierarchy of needs, with cost and quality falling below.

One other detail that appears problematic for many payers is the departure from ABA that some companies are taking. While some companies claim that they could bill under the same codes as ABA providers, the payers that we spoke with took a much more conservative approach, saying that the codes are defined by the service being delivered (e.g., ABA) and not the condition being treated (e.g., autism). One payer outright dismissed the idea of working with a non-ABA provider. Another said that they could envision working with an alternative provider, but under a pilot program that did not leverage existing codes.

Care Delivery Providers

The macros for providers are generally good given the high demand for services and attractive reimbursement. The biggest challenge facing providers is labor supply. Therapy is delivered in-person, on a 1:1 basis. As a result, the headcount requirement is high and it must be local (i.e., there is no opportunity for tele-servicing). In addition, the work is repetitive and stressful, leading to high burnout and turnover among the paraprofessional workforce (the average tenure is less than a year). As a result, while the macros are good, the operating risk is fairly high.

LRVHealth’s Takeaway Assessment

While the macros point to a strong business case for entering the market, we believe that a few additional cycles are needed to validate the new therapeutic approaches and align the incentives of all constituents. Throughout this process, we spoke with many people who characterized this exploding market as a “gold rush” and “predatory.” One person summed it up, saying the situation is “essentially a lot of capital chasing rich reimbursement, with less regard for children and families.” This may be an overly cynical view, but the hum of distrust for ABA is loud enough combined with examples like Elemy’s abrupt exit of multiple markets without regard for the children they served dampens our confidence in investing in this space at this point. Nevertheless, we are optimistic about the momentum in this space and the positive implications that could have on patients and their families.

[1] Digital Health Business & Technology funding database. Modern Healthcare.